Nuad Thai

Benchmarks for training in traditionnal / complementary and alternative medicine

WHO World Health Organisation

Abstracts :

I- Acknowledgements

WHO wishes to express its sincere gratitude to the Department for Development of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, for their support and recommendation of Dr Anchalee Chuthaputti, Thailand, for the preparation of the original text. A particular acknowledgement of appreciation is due to Dr Chuthaputti for her collaborative work.

A special note of thanks is extended to Dr Pennapa Subcharoen, former Deputy Director-General of the Department for Development of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand for her contributions to this document. She passed away in April 2008, just four months after attending the WHO Consultation on Manual Therapies in Milan, Italy.

WHO acknowledges its indebtedness to 244 reviewers, including experts and national authorities as well as professional and non-governmental organizations, in over 70 countries who provided comments and advice on the draft text.

Special thanks are due to the participants of the WHO Consultation on Manual Therapies (see Annex 2) who worked towards reviewing and finalizing the draft text, and to the WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine at the State University of Milan, Italy, in particular to Professor Umberto Solimene, Director, and Professor Emilio Minelli, Deputy Director, for their support to WHO in organizing the Consultation.

I-I-Preface

Integration of traditional medicine into national health systems

Traditional medicine has strong historical and cultural roots. Particularly in developing countries, traditional healers or practitioners would often be well- known and respected in the local community. However, more recently, the increasing use of traditional medicines combined with increased international mobility means that the practice of traditional medicines therapies and treatments is, in many cases, no longer limited to the countries of origin. This can make it difficult to identify qualified practitioners of traditional medicine in some countries.

One of the four main objectives of the WHO traditional medicine strategy 2002- 2005 was to support countries to integrate traditional medicine into their own health systems. In 2003, a WHO resolution (WHA56.31) on traditional medicine urged Member States, where appropriate, to formulate and implement national policies and regulations on traditional and complementary and alternative medicine to support their proper use. Further, Member States were urged to integrate TM/CAM into their national health-care systems, depending on their relevant national situations.

Ideally, countries would blend traditional and conventional ways of providing care in ways that make the most of the best features of each system and allow each to compensate for weaknesses in the other. Therefore, the 2009 WHO resolution (WHA62.13) on traditional medicine further urged Member States to consider, where appropriate, inclusion of traditional medicine in their national health systems. How this takes place would depend on national capacities, priorities, legislation and circumstances. It would have to consider evidence of safety, efficacy and quality.

Resolution WHA62.13 also urged Member States to consider, where appropriate, establishing systems for the qualification, accreditation or licensing of practitioners of traditional medicine. It urged Member States to assist practitioners in upgrading their knowledge and skills in collaboration with relevant providers of conventional care. The present series of benchmarks for basic training for selected types of TM/CAM care is part of the implementation of the WHO resolution. It concerns forms of TM/CAM that enjoy increasing popularity (Ayurveda, naturopathy, Nuad Thai, osteopathy, traditional Chinese medicine, Tuina, and Unani medicine)

These benchmarks reflect what the community of practitioners in each of these disciplines considers to be reasonable practice in training professionals to practice the respective discipline, considering consumer protection and patient safety as core to professional practice. They provide a reference point to which actual practice can be compared and evaluated. The series of seven documents is intended to:

Dr Xiaorui Zhang Coordinator, Traditional Medicine Department for Health System Governance and Service Delivery World Health Organizatio

II- Introduction

Nuad Thai may be regarded as part of the art, science and culture of Thailand, with a history dating back over six hundred years. “Nuad Thai” literally means “therapeutic Thai massage” and it is a branch of Thai traditional medical practice that provides non-medicinal based, manual therapy treatment for certain diseases and symptoms. In Thailand, when Nuad Thai is used for therapeutic or rehabilitative purposes, it is covered by the National Health Security System.

In other countries, Nuad Thai or “Thai massage” frequently refers to a type of Nuad Thai designed for health and relaxation. Such treatments can be found in spas and wellness centres in hotels and resorts all over the world. This type of Nuad Thai for health can also be used for the relief of general body aches and pains. In many areas, Nuad Thai also serves as a more cost effective treatment option for these symptoms, as traditional medicine practitioners are frequently more accessible, and the treatment they offer much less expensive, than imported medicines. The scope of this document will, however, focus only on Nuad Thai and the practice of the Nuad Thai practitioner at the professional level.

As Nuad Thai becomes accepted in other countries around the world, particularly in countries that neighbor Thailand, schools that offer training programmes in Nuad Thai have been established. This has led to concern about the safety and standards of training in Nuad Thai.

In Thailand, attempts have been made to develop the educational standard of Nuad Thai. In 2002 the Ministry of Public Health developed the Nuad Thai (800 hours) curriculum, while the Profession Commission (Thai Traditional Medicine branch) established a Nuad Thai Professional Curriculum in December 2007.

The WHO Consultation on Manual Therapies, held in Milan, Italy, in 2004 concluded that training should be increased to a minimum of 1,000 hours. More intensive training on health sciences and clinical practice should ensure that trainees have enough basic health science knowledge and clinical experience to be able to practice independently and safely. This is in line with the Professional Curriculum of Nuad Thai approved by the Profession Commission in the Branch of Thai Traditional Medicine in December 2007. In this curriculum, a student must take not less than two years to study and gain clinical experience in Nuad Thai before being eligible to undertake the licensing examination.

The resulting document, therefore, provides benchmarks for basic training of practitioners of Nuad Thai; models of training for trainees with different backgrounds; and a review of contraindications, so as to promote safe practice of Nuad Thai and minimize the risk of accidents. Together, these can serve as a reference for national authorities in establishing systems of training, examination and licensure that support the qualified practice of Nuad Thai.

II-I. Origin and principles of Nuad Thai

Nuad Thai for health and Nuad Thai therapy

Thai traditional massage, known in the Thai language as “Nuad Thai”, is Thailand’s traditional manual therapy. Nuad Thai is defined as “examination, diagnosis and treatment with the intention to prevent disease and promote health using pressure, circular pressure, squeezing, touching, bending, stretching, application of hot compresses, steam baths, traditional medicines, or other procedures of the art of Thai massage, all of which are based on the principles of Thai traditional medicine.” (1)

Nuad Thai is divided into two main types, namely, “Nuad Thai for health” and”Nuad Thai therapy”.

The origin of Nuad Thai is unclear. Massage has long been important to family health care, thought to go back to the health-care wisdom of Thai ancestors. Historical evidence shows that Nuad Thai was well accepted by the royal court and has been widely used by the Thai people since the Ayutthaya period (1350- 1767).

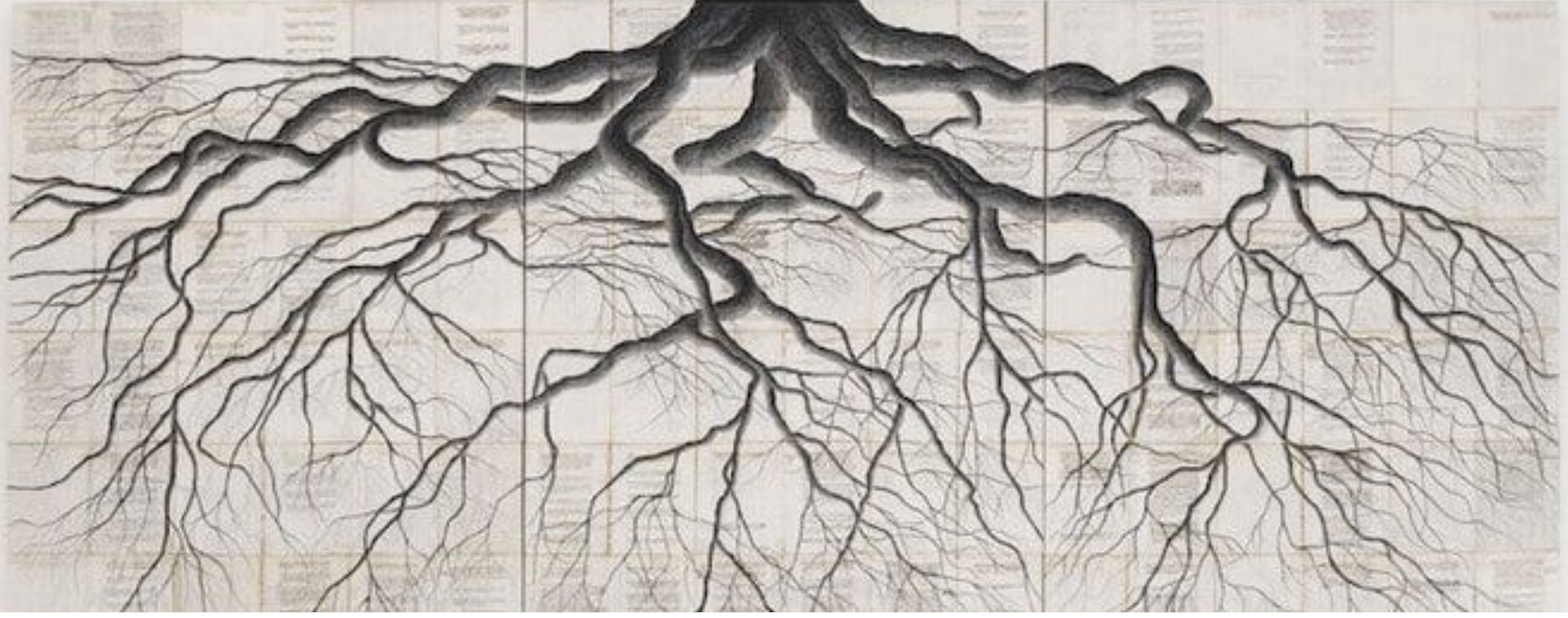

Nuad Thai became a formal body of knowledge during the 19th century. The knowledge of Nuad Thai was first compiled, organized systematically, and codified during the reign of King Rama III (1824-1851). The King ordered the inscription of 60 diagrams of Nuad Thai in order to provide knowledge of Nuad Thai for self-care by the Thai people. These showed sen lines and acupressure points on the body along with the explanation of the symptoms or diseases each massage spot could heal.

During the reign of King Rama V (1868-1910), the King ordered the compilation and systematic organization of knowledge about Thai traditional medicine. The Textbook of medicine, Royal edition, published in 1906, describes Nuad Thai. From the reign of King Rama VI (1910-1925) onwards (5), however, the role of Thai traditional medicine and massage began to decline, as the role of allopathic medicine increased following its introduction in Thailand during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the latter part of the 20th century the first school of applied Thai traditional medicine initiated the teaching of royal massage (Nuad Rajasamnak) as the manual therapy part of the three-year curriculum of applied Thai traditional medicine (6). Its royal massage curriculum was later adopted as a form of Nuad Thai by the National Institute of Thai Traditional Medicine within the Ministry of Public Health, and thereafter by some other colleges and universities. Meanwhile, nongovernmental organizations also played a role in reviving Thai massage. They provided training courses for the public and promoted its use in primary health care, specifically in reducing the need for various pain medications (5).

The 1990s saw an increased interest in Thai traditional medicine within the Ministry of Public Health of Thailand, and the establishment of the National Institute of Thai Traditional Medicine in 1993. The Institute reviewed and systematically described the styles of Nuad Thai taught at different schools and began to create the regulations and standards for Nuad Thai and the Nuad Thai curricula for the Ministry of Public Health of Thailand.

At the turn of the millennium, increasing public and private sector demand for qualified Nuad Thai practitioners led the Thai Ministry of Public Health to issue a Ministerial Regulation on 1 February 2001, officially making Nuad Thai a branch of Thai traditional medicine. The registration and licensing of practitioners, and the conditions and regulation of practice, are in accordance with the Practice of the Art of Healing Act, B.E. 2542 (1999) (1).

Thai traditional medicine is today incorporated into the health system of Thailand and Nuad Thai and the application of luk prakob (hot herbal compresses) are covered by the National Health Security System (7). At present, Thai people have easier access than ever before to Nuad Thai, as most public health-care facilities provide Nuad Thai.

II-II. Training of Nuad Thai practitioners

Regulating the practice of Nuad Thai and preventing practice by unqualified practitioners requires a proper system of training, examination and licensing. Benchmarks for training have to take into consideration the following:

Practitioners, experts and regulators of Nuad Thai consider the typical Type I programme as the relevant benchmark. This is a 1000 hours (minimum) training programme for those who have completed at least high-school education or equivalent, but have no prior health-care training or experience. On completion of this training programme, Nuad Thai practitioners will be able to practise as primary-contact health-care practitioners, either independently or as members of health-care teams in various settings. A typical applicant will have completed at least high-school education or equivalent, with appropriate training in basic sciences.

III-I Learning outcomes of a Type I programme

The Type I programme is intended to equip trainees for professional treatment of some commonly found painful symptoms or diseases of the musculoskeletal system, and prevention of complications of certain diseases exhibiting musculoskeletal symptoms. The curriculum is typically structured to provide the trainee with:

• a basic knowledge of health sciences related to Nuad Thai, including anatomy, physiology and pharmacology, with a focus on the neuromusculoskeletal and circulatory systems;

• a basic understanding of common clinical conditions of the neuromusculoskeletal system;

• a basic knowledge of Thai traditional medicine, with a focus on Nuad Thai, sen prathan sib, the sen pressure points related to each line, and the four elements, especially wind-related disorders;

• skill and expertise in Nuad Thai techniques ;

• the ability to decide whether the patient may safely and suitably betreated with Nuad Thai, or should be referred to another health professional or health-care facility;

• the capacity to identify contraindications to Nuad Thai or the need for particular precautions ;

• communication skills to interact with patients and their relatives, fellow practitioners, other health-care professionals and the general public;

• a high standard of professional ethics and the ability to follow a code of professional conduct.

III-II Health science components

The health science components of a typical Type I Nuad Thai programme includes:

A typical Type I Nuad Thai programme also addresses:

Generally, Nuad Thai is considered a safe manual therapy; however, some patients may experience minor adverse reactions, especially those who are receiving Nuad Thai for the first time and are not accustomed to the application of pressure on the trigger points to relieve myofascial pain syndrome. Adverse reactions may also occur if too much pressure is applied. Potential adverse reactions may include soreness, bruising, mild inflammation, or subcutaneous haemorrhage. Other reported adverse effects are said to include dizziness, vertigo or early or heavier menstruation.

Moderate adverse effects are said to be more frequent if practitioners lack experience, knowledge or skill, apply too much pressure, massage the wrong spot, or work on areas that are contraindicated. These moderate adverse reactions may include weakness and/or numbness in the extremities, fainting or cardiac arrhythmia due to pressure on the large arteries of the neck, oedema, severe soreness or inflammation. Moderate adverse effects reportedly may result in a need for the patient to seek medical attention (9).

Severe adverse reactions and accidents may happen if the wrong techniques are used, especially by inexperienced practitioners, or if Nuad Thai is applied to contraindicated areas of the body or in contraindicated cases. These severe adverse effects may include injured nerves, disc herniations, compressed spinal nerves, ischaemia of the brain or the heart, tearing of blood vessels, aneurysm of blood vessels, rupture of lymphatic vessels, or tearing of the intestine. These adverse reactions require immediate medical attention and hospitalization (9).

References

Boonsinsuk P. Research report on the use of traditional Thai massage to treat the painful condition of muscle and joint (in six government hospitals). Bangkok, Revival of Thai Traditional Massage Project, Health and Development Foundation, 1995:5-32.

Chatchawan U et al. Effectiveness of traditional Thai massage versus Swedish massage among patients with back pain associated with myofascial trigger points. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2005, 9:298-309.

Mackawan S et al. Effects of traditional Thai massage versus joint mobilization on substance P and pain perception in patients with non-specific low back pain. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2007, 11:9-16.

Ministry of Public Health Notification. Curricula of Thai Traditional Medicine of the Ministry of Public Health. Issued 26 August 2002.

Practice of the Art of Healing Act, B.E. 2542. Thai Royal Gazette, Vol. 116, Part 39 a, 18 May 1999.

Profession Commission in the Branch of Thai Traditional Medicine. Curriculum of The Practice of the Art of Healing in the Branch of Thai Traditional Medicine – NUAD THAI B.E. 2550. Professional Curriculum of Nuad Thai, approved on 19 December 2007.

Thepsongwat JJ et al. Effectiveness of the royal Thai massage for relief of muscle pain. Siriraj Medical Journal, 2006, 58:702-704.

The terms used in this document are defined as follows:

Luk Prakob (Hot herbal compress) (11,12)

A herbal ball made by wrapping various kinds of crushed herbs in a piece of cloth, tightly tied with a piece of cotton rope to make a ball, with a stick on top for handling. The herbal ball compress is steamed prior to application to an inflamed area of the body. The heat and the active constituents released from the herbs is intended to relieve pain and inflammation in the affected area.

Nuad Chaloeisak (folk massage) (13,14)

A type of Thai massage which originated in the common household and developed into styles of massage that use not only hands and fingers but also elbows, arms, knees, feet or heels. The massage techniques include applying pressure, stretching and manipulation. This style of Thai massage is commonly used for health and relaxation but it can also be used for therapeutic purposes.

Nuad Rajasamnak (royal or court massage) (15)

A style of Thai massage which originated as a form of Nuad Thai used in the royal court for members of the royal family and which was revived and formalized by the school of applied Thai traditional medicine. Royal massage emphasizes the use of the hands and fingers to apply pressure on the “sen pressure points” associated with the “sen lines”. Different positions of the practitioner and positions of his/her fingers and palms, the angle of the arms, the position of hands or fingers on the patient’s body, the pressure applied and the duration of application are all parts of an appropriate royal massage technique.

Nuad Thai (16)

Examination, diagnosis, and treatment, with the intention of preventing disease and promoting health, using: pressure; circular pressure; squeezing; touching; bending; stretching; application of hot compresses; steam baths; or other procedures in the art of traditional Thai massage or the use of traditional medicines, all of which are based on the principles of Thai traditional medicine.

Nuad Thai therapy (15,17,18)

A type of therapeutic Thai massage intended to cure or relieve musculoskeletal disorders and painful symptoms in various parts of the body, e.g. myofascial pain syndrome or tension headache, and for rehabilitative purposes to prevent or relieve muscle spasm and joint stiffness, e.g. in patients with paralysis, paresis or Parkinson’s disease.

Rusi dutton (19)

A traditional Thai stretching exercise used for health promotion, disease prevention, and the rehabilitation of some minor disorders. Ruesi means “hermit” and dud ton means “body stretching exercise”.

Sen pressure point (20)

Points on the sen lines associated with specific diseases or symptoms. The application of pressure by way of Nuad Thai is intended to help relieve such diseases or symptoms.

Tard (the four elements)

These are the basic elements that are traditionally believed to be the components of the living body in Thai traditional medicine. According to Thai traditional medicine theory, there are four major elements: earth, wind, water and fire.

Thai spaya

The term “spaya” means being in a healthy environment and is derived from the Thai word “sabai”, meaning “to experience well-being, be comfortable or healthy.” This term is now used to describe a type of spa service in Thailand based on Thai traditional health care, part of which is Nuad Thai .

Annex 2: WHO Consultation on Manual Therapies, Milan, Italy, 12–14 November 2007: list of participants

Participants

Mr Peter Arhin, Director, Traditional and Alternative Medicine Directorate,

Ministry of Health, Accra, Ghana

Dr Iracema de Almeida Benevides, Consultant and Medical Advisor, National Policy of Integrative and Complementary Practices, Ministry of Health, Brasilia - DF, Brazil

Dr Anchalee Chuthaputti, Senior Pharmacist, Department for Development of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand [Co-Rapporteur]

Dr Franco Cracolici, Federazione Italiana Scuole Tuina e Qigong, Firenze, Italy Dr Alessandro Discalzi, Directorate-General, Family and Social Solidarity,

Lombardy Region, Milan, Italy

Dr Mona M. Hejres, Education Medical Registrar, Office of Licensure and Registration, Ministry of Health, Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain

Dr Giovanni Leonardi, General Director, Human Resources and Health Professions, Ministry of Health, Rome, Italy

Professor Yutang Li, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, Nanjing University of Traditional Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China

Professor Emilio Minelli, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, Centre of Research in Bioclimatology, Biotechnologies and Natural Medicine, State University of Milan, Milan, Italy

Dr Nguyen Thi Kim Dung Director, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, National Hospital of Traditional Medicine, Hanoi, Viet Nam

Dr Susanne Nordling, Chairman, Nordic Co-operation Committee for Non- conventional Medicine, Sollentuna, Sweden [Co-Chairperson]

Dr Hieng Punley, Director, National Center of Traditional Medicine, Ministry of Health, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Dr Léon Ranaivo-Harimanana, Head of Clinical Trial Department in Centre National d’Application des Recherches Pharmaceutiques, Ambodivoanjo, Antananarivo, Madagascar

Ms Lucia Scrabbi, Planning Unit Directorate-General of Health, Lombardy Region, Milan, Italy

Professor Umberto Solimene, Director, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, Centre of Research in Bioclimatology, Biotechnologies and Natural Medicine, State University of Milan, Milan, Italy

*Dr Pennapa Subcharoen, Health Supervisor, Office of the Health Inspector, General Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand

Dr Chaiyanan Thayawiwat, Director, Hua Hin Hospital, Amphur Hua Hin, Prachuapkhirikhan, Thailand

Dr Sounaly Themy, Medical Doctor, Traditional Therapies, Traditional Medicine Research Centre, Ministry of Health, Vientiane, Lao People's Democratic Republic

Dr Yong-Jun Wang, Director, Orthopaedics Department, Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, China

Dr Jidong Wu, President, Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom

Professor Shan Wu Moxibustion Department Guangzhou Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province China

Professor Yunxiang Xu, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China

Professor Charlie Changli Xue, Director, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, Division of Chinese Medicine, School of Health Sciences, RMIT University, Bundoora, Victoria, Australia [Co-Rapporteur]

Dr Je-Pil Yoon, Director, Department of International Affairs, Association of Korean Oriental Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Dr Qi Zhang, Director-General, Department of International Cooperation, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China [Co-Chairperson]

Local Secretariat

Dr Maurizio Italiano, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, Centre of Research in Medical Bioclimatology, Biotechnologies and Natural Medicines, State University of Milan, Milan, Italy

* It was with great sorrow that we learned of the death of Professor Subcharoen in April 2008. Her great contributions to the work of WHO, especially in the development of this document on basic training in Nuad Thai therapy, will always be remembered.

WHO Secretariat

Dr Samvel Azatyan, Technical Officer, Department of Technical Cooperation for Essential Drugs and Traditional Medicine, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Dr Houxin Wu, Technical Officer, Traditional Medicine, Department of Technical Cooperation for Essential Drugs and Traditional Medicine, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Dr Xiaorui Zhang, Coordinator, Traditional Medicine, Department of Technical Cooperation for Essential Drugs and Traditional Medicine, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland "

Plus d'infos:>>>

Benchmarks for training in traditionnal / complementary and alternative medicine

WHO World Health Organisation

Abstracts :

I- Acknowledgements

WHO wishes to express its sincere gratitude to the Department for Development of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, for their support and recommendation of Dr Anchalee Chuthaputti, Thailand, for the preparation of the original text. A particular acknowledgement of appreciation is due to Dr Chuthaputti for her collaborative work.

A special note of thanks is extended to Dr Pennapa Subcharoen, former Deputy Director-General of the Department for Development of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand for her contributions to this document. She passed away in April 2008, just four months after attending the WHO Consultation on Manual Therapies in Milan, Italy.

WHO acknowledges its indebtedness to 244 reviewers, including experts and national authorities as well as professional and non-governmental organizations, in over 70 countries who provided comments and advice on the draft text.

Special thanks are due to the participants of the WHO Consultation on Manual Therapies (see Annex 2) who worked towards reviewing and finalizing the draft text, and to the WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine at the State University of Milan, Italy, in particular to Professor Umberto Solimene, Director, and Professor Emilio Minelli, Deputy Director, for their support to WHO in organizing the Consultation.

I-I-Preface

Integration of traditional medicine into national health systems

Traditional medicine has strong historical and cultural roots. Particularly in developing countries, traditional healers or practitioners would often be well- known and respected in the local community. However, more recently, the increasing use of traditional medicines combined with increased international mobility means that the practice of traditional medicines therapies and treatments is, in many cases, no longer limited to the countries of origin. This can make it difficult to identify qualified practitioners of traditional medicine in some countries.

One of the four main objectives of the WHO traditional medicine strategy 2002- 2005 was to support countries to integrate traditional medicine into their own health systems. In 2003, a WHO resolution (WHA56.31) on traditional medicine urged Member States, where appropriate, to formulate and implement national policies and regulations on traditional and complementary and alternative medicine to support their proper use. Further, Member States were urged to integrate TM/CAM into their national health-care systems, depending on their relevant national situations.

Ideally, countries would blend traditional and conventional ways of providing care in ways that make the most of the best features of each system and allow each to compensate for weaknesses in the other. Therefore, the 2009 WHO resolution (WHA62.13) on traditional medicine further urged Member States to consider, where appropriate, inclusion of traditional medicine in their national health systems. How this takes place would depend on national capacities, priorities, legislation and circumstances. It would have to consider evidence of safety, efficacy and quality.

Resolution WHA62.13 also urged Member States to consider, where appropriate, establishing systems for the qualification, accreditation or licensing of practitioners of traditional medicine. It urged Member States to assist practitioners in upgrading their knowledge and skills in collaboration with relevant providers of conventional care. The present series of benchmarks for basic training for selected types of TM/CAM care is part of the implementation of the WHO resolution. It concerns forms of TM/CAM that enjoy increasing popularity (Ayurveda, naturopathy, Nuad Thai, osteopathy, traditional Chinese medicine, Tuina, and Unani medicine)

These benchmarks reflect what the community of practitioners in each of these disciplines considers to be reasonable practice in training professionals to practice the respective discipline, considering consumer protection and patient safety as core to professional practice. They provide a reference point to which actual practice can be compared and evaluated. The series of seven documents is intended to:

- support countries to establish systems for the qualification, accreditation or licensing of practitioners of traditional medicine;

- assist practitioners in upgrading their knowledge and skills in collaboration with providers of conventional care;

- allow better communication between providers of conventional and traditional care as well as other health professionals, medical students and relevant researchers through appropriate training programmes;

- support integration of traditional medicine into the national health system.

The documents describe models of training for trainees with different backgrounds. They list contraindications identified by the community of practitioners, so as to promote safe practice and minimize the risk of accidents.

- The most elaborated material to establish benchmarks comes from the countries where the various forms of traditional medicine under consideration originated. These countries have established formal education or national requirements for licensure or qualified practice. Any relevant benchmarks must refer to these national standards and requirements.

- The first stage of drafting of this series of documents was delegated to the national authorities in the countries of origin of each of the respective forms of traditional, complementary or alternative medicine discussed. These drafts were then, in a second stage, distributed to more than 300 reviewers in more than 140 countries. These reviewers included experts and national health authorities,

Dr Xiaorui Zhang Coordinator, Traditional Medicine Department for Health System Governance and Service Delivery World Health Organizatio

II- Introduction

Nuad Thai may be regarded as part of the art, science and culture of Thailand, with a history dating back over six hundred years. “Nuad Thai” literally means “therapeutic Thai massage” and it is a branch of Thai traditional medical practice that provides non-medicinal based, manual therapy treatment for certain diseases and symptoms. In Thailand, when Nuad Thai is used for therapeutic or rehabilitative purposes, it is covered by the National Health Security System.

In other countries, Nuad Thai or “Thai massage” frequently refers to a type of Nuad Thai designed for health and relaxation. Such treatments can be found in spas and wellness centres in hotels and resorts all over the world. This type of Nuad Thai for health can also be used for the relief of general body aches and pains. In many areas, Nuad Thai also serves as a more cost effective treatment option for these symptoms, as traditional medicine practitioners are frequently more accessible, and the treatment they offer much less expensive, than imported medicines. The scope of this document will, however, focus only on Nuad Thai and the practice of the Nuad Thai practitioner at the professional level.

As Nuad Thai becomes accepted in other countries around the world, particularly in countries that neighbor Thailand, schools that offer training programmes in Nuad Thai have been established. This has led to concern about the safety and standards of training in Nuad Thai.

In Thailand, attempts have been made to develop the educational standard of Nuad Thai. In 2002 the Ministry of Public Health developed the Nuad Thai (800 hours) curriculum, while the Profession Commission (Thai Traditional Medicine branch) established a Nuad Thai Professional Curriculum in December 2007.

The WHO Consultation on Manual Therapies, held in Milan, Italy, in 2004 concluded that training should be increased to a minimum of 1,000 hours. More intensive training on health sciences and clinical practice should ensure that trainees have enough basic health science knowledge and clinical experience to be able to practice independently and safely. This is in line with the Professional Curriculum of Nuad Thai approved by the Profession Commission in the Branch of Thai Traditional Medicine in December 2007. In this curriculum, a student must take not less than two years to study and gain clinical experience in Nuad Thai before being eligible to undertake the licensing examination.

The resulting document, therefore, provides benchmarks for basic training of practitioners of Nuad Thai; models of training for trainees with different backgrounds; and a review of contraindications, so as to promote safe practice of Nuad Thai and minimize the risk of accidents. Together, these can serve as a reference for national authorities in establishing systems of training, examination and licensure that support the qualified practice of Nuad Thai.

II-I. Origin and principles of Nuad Thai

Nuad Thai for health and Nuad Thai therapy

Thai traditional massage, known in the Thai language as “Nuad Thai”, is Thailand’s traditional manual therapy. Nuad Thai is defined as “examination, diagnosis and treatment with the intention to prevent disease and promote health using pressure, circular pressure, squeezing, touching, bending, stretching, application of hot compresses, steam baths, traditional medicines, or other procedures of the art of Thai massage, all of which are based on the principles of Thai traditional medicine.” (1)

Nuad Thai is divided into two main types, namely, “Nuad Thai for health” and”Nuad Thai therapy”.

- “Nuad Thai for health” is usually applied all over the body to help relax muscle tension. Although Nuad Thai for health can help relieve general body aches and pains, it is intended for relaxation and health promotion rather than for therapeutic purposes. The use of Nuad Thai for health is not considered to be the practice of a healing art. (2,3,4)

- “Nuad Thai therapy” is intended to (i) cure or relieve musculoskeletal disorders and painful symptoms in various parts of the body, e.g. myofascial pain syndrome or tension headache, and (ii) prevent or relieve muscle spasm and joint stiffness, e.g. in patients with paralysis, paresis or Parkinson’s disease. This therapy is symptom-oriented Nuad Thai that concentrates on massaging the affected body part and related areas of the body for therapeutic purposes.

This document deals only with “Nuad Thai therapy”, and does not address “Nuad Thai for health”. As part of Thai traditional medicine, Nuad Thai follows the basic principle that the human body is composed of the four elements (tard), i.e. earth, water, wind and fire. When the four elements of the body are in equilibrium, the person will be healthy. In contrast, if an imbalance in these elements occurs, i.e. if there is deficit, excess, or a malfunction in any of the four elements, the person will become ill. The wind element represents movement and the flow of energy. The wind and its energy are believed to flow along the “sen”, or lines. According to the inscription of massage diagrams at Wat Pho (the Temple of the Reclining Buddha in Thailand) and original traditional textbooks of Nuad Thai, the human body is composed of 72 000 sen lines, of which there are ten principal sen lines called “sen sib” or “sen prathan sib”. Both Nuad Thai for health and Nuad Thai therapy are based on the principle of sen sib. According to the principles of Thai traditional medicine and sen sib, if the flow of energy or wind along sen lines is obstructed or becomes stagnant, diseases and symptoms will result. There are several diseases and symptoms that are related to the sen lines. Nuad Thai on sen lines, and on acupressure points on the sen lines, will relieve the obstruction and promote the flow of energy and wind along the sen lines, and is therefore believed to help relieve various diseases and symptoms (5,8).

The origin of Nuad Thai is unclear. Massage has long been important to family health care, thought to go back to the health-care wisdom of Thai ancestors. Historical evidence shows that Nuad Thai was well accepted by the royal court and has been widely used by the Thai people since the Ayutthaya period (1350- 1767).

Nuad Thai became a formal body of knowledge during the 19th century. The knowledge of Nuad Thai was first compiled, organized systematically, and codified during the reign of King Rama III (1824-1851). The King ordered the inscription of 60 diagrams of Nuad Thai in order to provide knowledge of Nuad Thai for self-care by the Thai people. These showed sen lines and acupressure points on the body along with the explanation of the symptoms or diseases each massage spot could heal.

During the reign of King Rama V (1868-1910), the King ordered the compilation and systematic organization of knowledge about Thai traditional medicine. The Textbook of medicine, Royal edition, published in 1906, describes Nuad Thai. From the reign of King Rama VI (1910-1925) onwards (5), however, the role of Thai traditional medicine and massage began to decline, as the role of allopathic medicine increased following its introduction in Thailand during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the latter part of the 20th century the first school of applied Thai traditional medicine initiated the teaching of royal massage (Nuad Rajasamnak) as the manual therapy part of the three-year curriculum of applied Thai traditional medicine (6). Its royal massage curriculum was later adopted as a form of Nuad Thai by the National Institute of Thai Traditional Medicine within the Ministry of Public Health, and thereafter by some other colleges and universities. Meanwhile, nongovernmental organizations also played a role in reviving Thai massage. They provided training courses for the public and promoted its use in primary health care, specifically in reducing the need for various pain medications (5).

The 1990s saw an increased interest in Thai traditional medicine within the Ministry of Public Health of Thailand, and the establishment of the National Institute of Thai Traditional Medicine in 1993. The Institute reviewed and systematically described the styles of Nuad Thai taught at different schools and began to create the regulations and standards for Nuad Thai and the Nuad Thai curricula for the Ministry of Public Health of Thailand.

At the turn of the millennium, increasing public and private sector demand for qualified Nuad Thai practitioners led the Thai Ministry of Public Health to issue a Ministerial Regulation on 1 February 2001, officially making Nuad Thai a branch of Thai traditional medicine. The registration and licensing of practitioners, and the conditions and regulation of practice, are in accordance with the Practice of the Art of Healing Act, B.E. 2542 (1999) (1).

Thai traditional medicine is today incorporated into the health system of Thailand and Nuad Thai and the application of luk prakob (hot herbal compresses) are covered by the National Health Security System (7). At present, Thai people have easier access than ever before to Nuad Thai, as most public health-care facilities provide Nuad Thai.

II-II. Training of Nuad Thai practitioners

Regulating the practice of Nuad Thai and preventing practice by unqualified practitioners requires a proper system of training, examination and licensing. Benchmarks for training have to take into consideration the following:

- content of the training;

- method of the training;

- to whom the training is to be provided and by whom;

- the roles and responsibilities of the future practitioner;

- the level of education required in order to undertake training.

Nuad Thai experts distinguish three types of Tuina training in function of prior training and clinical experience of trainees.

Type I training programmes are aimed at those who have completed high-school education or equivalent, but have no prior medical or other health-care training or experience. These trainees are required to study the full Nuad Thai programme. This is typically a full-time or equivalent training of a minimum of 1000 hours.

Type II training programmes are aimed at those with medical or other health-care training who wish to become recognized Nuad Thai practitioners. These programmes can be shorter if trainees have already covered some of the components in their earlier health-care training and experience. A typical programme will last approximately 800 hours.

Type III training programmes are limited programmes providing upgrading and qualification for existing Nuad Thai practitioners who have had previous training and work experience in Nuad Thai, but who have not yet received formal full Nuad Thai training.

Upon completion of the programmes, all students must meet the minimum competency requirements for Nuad Thai practitioners .

Practitioners, experts and regulators of Nuad Thai consider the typical Type I programme as the relevant benchmark. This is a 1000 hours (minimum) training programme for those who have completed at least high-school education or equivalent, but have no prior health-care training or experience. On completion of this training programme, Nuad Thai practitioners will be able to practise as primary-contact health-care practitioners, either independently or as members of health-care teams in various settings. A typical applicant will have completed at least high-school education or equivalent, with appropriate training in basic sciences.

III-I Learning outcomes of a Type I programme

The Type I programme is intended to equip trainees for professional treatment of some commonly found painful symptoms or diseases of the musculoskeletal system, and prevention of complications of certain diseases exhibiting musculoskeletal symptoms. The curriculum is typically structured to provide the trainee with:

• a basic knowledge of health sciences related to Nuad Thai, including anatomy, physiology and pharmacology, with a focus on the neuromusculoskeletal and circulatory systems;

• a basic understanding of common clinical conditions of the neuromusculoskeletal system;

• a basic knowledge of Thai traditional medicine, with a focus on Nuad Thai, sen prathan sib, the sen pressure points related to each line, and the four elements, especially wind-related disorders;

• skill and expertise in Nuad Thai techniques ;

• the ability to decide whether the patient may safely and suitably betreated with Nuad Thai, or should be referred to another health professional or health-care facility;

• the capacity to identify contraindications to Nuad Thai or the need for particular precautions ;

• communication skills to interact with patients and their relatives, fellow practitioners, other health-care professionals and the general public;

• a high standard of professional ethics and the ability to follow a code of professional conduct.

III-II Health science components

The health science components of a typical Type I Nuad Thai programme includes:

- basic anatomy;

- basic physiology;

- basic herboristery;

- basic clinical sciences;

- basic musculoskeletal disorders;

- basic examination and assessment of the musculoskeletal system;

- evaluation of painful symptoms

- theories of Thai traditional medicine;

- history of Thai traditional medicine and the four elements;

- theory of causes of disease as related to seasons, age, time, place,

symptoms and behaviour; - basic Thai traditional pharmacy, specifically commonly used herbal

medicines for bone, tendon and muscle disorders, herbal baths, and

herbal compresses; - basic Thai traditional medicine diagnosis and treatment composed of

preliminary diagnosis, characteristics of the four elements, and herbal medicines suitable for each element, disease and symptom. - III-IV- Nuad Thai philosophy

- history, body of knowledge and application of Nuad Thai;

- health benefits, values and various styles of Nuad Thai, and its use in the

health-care system; - the ten principal sen lines and their structure, energy flow and

characteristics as well as their relationship to disease, the sen pressure points for treating various ailments, the types of sen pressure points on sen lines, the use of the beginning points of sen sib for Nuad Thai; - principles, procedures, potential benefits, contraindications and methods of basic Nuad Thai for application on the back, outer and inner leg, shoulder and head;

- application of Nuad Thai in the treatment of various symptoms and diseases;

- examination and diagnosis of energy lines and wind-related disorders based on the sen sib theory;

- causes of symptoms and diseases and Nuad Thai for the treatment of various conditions;

- Nuad Thai for rehabilitation of various disabilities in different age groups and for the restoration of various functions;

- Nuad Thai for the feet including the use of reflexive points on the foot to treat diseases and their affect on the function of various organs;

- Nuad Thai techniques for health promotion and enhancement of physical fitness of athletes and treatment of patients suffering from sports injuries;

- Nuad Thai for antenatal, postnatal and child care, including disorders of mother and child before and after delivery as well as use of Nuad Thai for maternal care III-VThai traditional medicine component

- The Thai traditional medicine component of a typical Type I Nuad Thai programme includes:

- use of oils for the treatment of inflammation, muscle sprains and tendinitis, procedures and benefits of aromatherapy, and the extraction of essential oils from herbs;

- meaning, concept and classification of Thai spaya and the role of Nuad Thai in Thai spaya;

- philosophy, concepts and practice of basic meditation; procedures, benefits and precautions of ruesi dud ton (Thai traditional stretching exercises).

A typical Type I Nuad Thai programme also addresses:

- professional regulations;

- national health system;

- clinical record-keeping;

- practice management;

- activities to promote teamwork;

- principles of communication;

- cultural sensitivity;

- professional ethics;

- art of service.

- In a typical Type I Nuad Thai programme each student practices Nuad Thai under supervision at field sites in at least 100 cases of specific symptoms and diseases. These cases include all of the following symptoms/conditions:

- patients with pain in the head area;

- patients with pain or sprains in the neck;

- patients with pain, stiffness or numbness in the shoulder or scapula;

- patients with pain or sprains in the arm, elbow, wrist or hand;

- patients with pain, sprains or numbness in the back, waist, sides of the

torso or abdomen; - patients with pain, stiffness or sprains in the hip joint, hip area or lower

back; - patients with pain, sprains, stiffness or numbness in the knee;

- patients with pain, sprains, stiffness or numbness in the leg, ankle or feet;

- paralysed or paretic patients;

- women before and after childbirth.

IV. Safety issues - Nuad Thai experts and practitioners consider it important, in order to increase safety and decrease the risk of adverse effects that might occur in patients after Nuad Thai, that all practitioners, including other traditional medicine practitioners, medical doctors and other health-care professionals, should examine and screen patients for any contraindications before treating them or referring them for Nuad Thai (9).

- V-I Precautions and contraindications

Nuad Thai practitioners consider that Nuad Thai is contraindicated if the patient has any of the following conditions (9): - sharp pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness along the arms or the legs which might indicate acute herniated disc;

- fever over 38.5°C;

- hypertension with systolic blood pressure above 160 mmHg and/or

diastolic blood pressure above 100 mmHg combined with syncope,

tachycardia, headache, nausea or vomiting; - recent (less than 1 month) surgery;

- severe osteoporosis;

- communicable diseases, especially airborne types, e.g. influenza,

tuberculosis.

Massage in the hypogastric region is contraindicated for pregnant women with morning sickness, watery or bloody vaginal discharge or severe oedema of the extremities, or if the movement of the baby decreases for more than 24 hours. Nuad Thai is also contraindicated in areas of the body that have the following problems:- fresh wounds, open wounds or recent injury;

- vascular problems, e.g. varicoses, thrombosis, ulceration, atherosclerotic

plaque, aneurysm; - serious joint or bone problems, e.g. broken bone, dislocation, severe

osteoporosis, multiple myeloma, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid

arthritis with joint deformity or deviation; - skin diseases or dermal infections, e.g. cellulitis, chronic wounds, herpes

simplex, herpes zoster, tinea; - deep vein thrombosis (10);

- burns;

- inflammation;

- cancer.

- • patients with vascular disease, e.g. aneurysm, vasculitis, atherosclerosis;

- hypertensive patients with systolic blood pressure over 160 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure over 100 mmHg not combined with syncope, tachycardia, headache, nausea or vomiting;

- patients with osteoporosis;

- patients with abnormal blood clotting or excessive bleeding who are

taking thrombolytic agents; - joint dislocation;

- areas of the body where metal pins, steel plates, screws or prosthetic

points have been inserted; - areas where wounds are not completely healed;

- broken skin;

- skin grafts.

Generally, Nuad Thai is considered a safe manual therapy; however, some patients may experience minor adverse reactions, especially those who are receiving Nuad Thai for the first time and are not accustomed to the application of pressure on the trigger points to relieve myofascial pain syndrome. Adverse reactions may also occur if too much pressure is applied. Potential adverse reactions may include soreness, bruising, mild inflammation, or subcutaneous haemorrhage. Other reported adverse effects are said to include dizziness, vertigo or early or heavier menstruation.

Moderate adverse effects are said to be more frequent if practitioners lack experience, knowledge or skill, apply too much pressure, massage the wrong spot, or work on areas that are contraindicated. These moderate adverse reactions may include weakness and/or numbness in the extremities, fainting or cardiac arrhythmia due to pressure on the large arteries of the neck, oedema, severe soreness or inflammation. Moderate adverse effects reportedly may result in a need for the patient to seek medical attention (9).

Severe adverse reactions and accidents may happen if the wrong techniques are used, especially by inexperienced practitioners, or if Nuad Thai is applied to contraindicated areas of the body or in contraindicated cases. These severe adverse effects may include injured nerves, disc herniations, compressed spinal nerves, ischaemia of the brain or the heart, tearing of blood vessels, aneurysm of blood vessels, rupture of lymphatic vessels, or tearing of the intestine. These adverse reactions require immediate medical attention and hospitalization (9).

References

- Ministry of Public Health Notification B.E. 2544. Addition of Thai Massage as a Branch of Practice of Thai Traditional Medicine. Issued 1 February 2001. In: Thai Royal Gazette. Vol. 118, Part 25d, 27 March 2001.

- Benjamongkolwaree P. Massage for whole body relaxation. In: Nuad Thai for Health. Bangkok, Moh Chao Ban Publishing, Volume 1, 2nd ed., 2002.

- References

15

Benchmarks for training in Nuad Thai - Leewanun C. Massage for health. In: Apiwatanaporn N, Teerawan S, Iamsupasit S, eds. Information for operators of spa for health business. 3rd ed. Bangkok, Department of Health Service Support, Ministry of Public Health, 2008:87-102.

- Foundation for the Revival and Promotion of Thai Traditional Medicine, A yurvej School. T extbook of Thai T raditional Manual Therapy (Nuad Rajasamnak). Bangkok, Piganesh Printing Center, 2005.

- Ministry of Public Health Notification B.E. 2544. Addition of Thai Massage as a Branch of Practice of Thai Traditional Medicine. Issued 1 February 2001. In: Thai Royal Gazette. Vol. 118, Part 25d, 27 March 2001.

- Marble Inscriptions of Herbal Remedies at Wat Phra Chetupon Wimon Manklaram (Wat Pho), Phra NaKhon (Bangkok), Inscribed under the Royal Command of King Rama III in B.E. 2375 (AD1832), The Complete Edition.

- Tantipidok Y, ed. Textbook of Nuad Thai, Volume 1. Bangkok, Health & Development Foundation, 2007.

- Subcharoen P, ed. Move your body, make you healthy with Thai traditional exercise (15 Basic postures of ruesi dud ton). Bangkok, War Veterans Administration Printing, 3rd ed., 2003.

- King Rama, the Fifth Medical Classic. Volume 2. Bangkok, The Fine Arts Department, 1999:74-123.

Boonsinsuk P. Research report on the use of traditional Thai massage to treat the painful condition of muscle and joint (in six government hospitals). Bangkok, Revival of Thai Traditional Massage Project, Health and Development Foundation, 1995:5-32.

Chatchawan U et al. Effectiveness of traditional Thai massage versus Swedish massage among patients with back pain associated with myofascial trigger points. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2005, 9:298-309.

Mackawan S et al. Effects of traditional Thai massage versus joint mobilization on substance P and pain perception in patients with non-specific low back pain. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2007, 11:9-16.

Ministry of Public Health Notification. Curricula of Thai Traditional Medicine of the Ministry of Public Health. Issued 26 August 2002.

Practice of the Art of Healing Act, B.E. 2542. Thai Royal Gazette, Vol. 116, Part 39 a, 18 May 1999.

Profession Commission in the Branch of Thai Traditional Medicine. Curriculum of The Practice of the Art of Healing in the Branch of Thai Traditional Medicine – NUAD THAI B.E. 2550. Professional Curriculum of Nuad Thai, approved on 19 December 2007.

Thepsongwat JJ et al. Effectiveness of the royal Thai massage for relief of muscle pain. Siriraj Medical Journal, 2006, 58:702-704.

- Revival of Nuad Thai Project. Handbook of Nuad Thai. Bangkok, Ruan Kaew Printing, 1994.

- Institute of Thai Traditional Medicine. Thai Traditional Medicine Curricula of the Ministry of Public Health. Bangkok, Beyond Publishing, 1st ed. 2008:129- 144.

- Tantipidok Y, ed. Textbook of Nuad Thai, Volume I. Bangkok, Health & Development Foundation. 3rd ed., 2007.

- Society of Ayurveda Doctors of Applied Thai Traditional Medicine. Two decades of Ayurved. Bangkok, Chamchuree Product, 1999.

- Notification of the National Health Security Committee. Thai Traditional Medicine Services. Issued 21 June 2002.

- Dewises K, ed. Handbook of Thai massage training. Bangkok, V eteran Administration Printing, 1999.

- Leewanun C. Massage for health. In: Apiwatanaporn N, Teerawan S, Iamsupasit S, eds. Information for operators of spa for health business. 3rd ed., Bangkok, Department of Health Service Support, Ministry of Public Health. 2008:87-102.

- Chierakul N, Jakarapanichakul D, Phanchaipetch T. An unexpected complication of traditional Thai massage. Siriraj Hospital Gazette, 2003, 55:167-170.

- The Royal Institute. The Royal Institute Dictionary B.E. 2542. Bangkok, Nanmee Books Publication, 1999:1024.

- Sittitanyakit K., Termwiset P, eds. Manual on the Use of Thai Traditional Medicine for the Health Care of People. Bangkok, War Veterans Administration Printing, 2004:144-6.

- Ministry of Public Health Notification. Thai traditional medicine curricula of the Ministry of Public Health. Issued on 26 August 2002.

The terms used in this document are defined as follows:

Luk Prakob (Hot herbal compress) (11,12)

A herbal ball made by wrapping various kinds of crushed herbs in a piece of cloth, tightly tied with a piece of cotton rope to make a ball, with a stick on top for handling. The herbal ball compress is steamed prior to application to an inflamed area of the body. The heat and the active constituents released from the herbs is intended to relieve pain and inflammation in the affected area.

Nuad Chaloeisak (folk massage) (13,14)

A type of Thai massage which originated in the common household and developed into styles of massage that use not only hands and fingers but also elbows, arms, knees, feet or heels. The massage techniques include applying pressure, stretching and manipulation. This style of Thai massage is commonly used for health and relaxation but it can also be used for therapeutic purposes.

Nuad Rajasamnak (royal or court massage) (15)

A style of Thai massage which originated as a form of Nuad Thai used in the royal court for members of the royal family and which was revived and formalized by the school of applied Thai traditional medicine. Royal massage emphasizes the use of the hands and fingers to apply pressure on the “sen pressure points” associated with the “sen lines”. Different positions of the practitioner and positions of his/her fingers and palms, the angle of the arms, the position of hands or fingers on the patient’s body, the pressure applied and the duration of application are all parts of an appropriate royal massage technique.

Nuad Thai (16)

Examination, diagnosis, and treatment, with the intention of preventing disease and promoting health, using: pressure; circular pressure; squeezing; touching; bending; stretching; application of hot compresses; steam baths; or other procedures in the art of traditional Thai massage or the use of traditional medicines, all of which are based on the principles of Thai traditional medicine.

Nuad Thai therapy (15,17,18)

A type of therapeutic Thai massage intended to cure or relieve musculoskeletal disorders and painful symptoms in various parts of the body, e.g. myofascial pain syndrome or tension headache, and for rehabilitative purposes to prevent or relieve muscle spasm and joint stiffness, e.g. in patients with paralysis, paresis or Parkinson’s disease.

Rusi dutton (19)

A traditional Thai stretching exercise used for health promotion, disease prevention, and the rehabilitation of some minor disorders. Ruesi means “hermit” and dud ton means “body stretching exercise”.

Sen pressure point (20)

Points on the sen lines associated with specific diseases or symptoms. The application of pressure by way of Nuad Thai is intended to help relieve such diseases or symptoms.

Tard (the four elements)

These are the basic elements that are traditionally believed to be the components of the living body in Thai traditional medicine. According to Thai traditional medicine theory, there are four major elements: earth, wind, water and fire.

Thai spaya

The term “spaya” means being in a healthy environment and is derived from the Thai word “sabai”, meaning “to experience well-being, be comfortable or healthy.” This term is now used to describe a type of spa service in Thailand based on Thai traditional health care, part of which is Nuad Thai .

Annex 2: WHO Consultation on Manual Therapies, Milan, Italy, 12–14 November 2007: list of participants

Participants

Mr Peter Arhin, Director, Traditional and Alternative Medicine Directorate,

Ministry of Health, Accra, Ghana

Dr Iracema de Almeida Benevides, Consultant and Medical Advisor, National Policy of Integrative and Complementary Practices, Ministry of Health, Brasilia - DF, Brazil

Dr Anchalee Chuthaputti, Senior Pharmacist, Department for Development of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand [Co-Rapporteur]

Dr Franco Cracolici, Federazione Italiana Scuole Tuina e Qigong, Firenze, Italy Dr Alessandro Discalzi, Directorate-General, Family and Social Solidarity,

Lombardy Region, Milan, Italy

Dr Mona M. Hejres, Education Medical Registrar, Office of Licensure and Registration, Ministry of Health, Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain

Dr Giovanni Leonardi, General Director, Human Resources and Health Professions, Ministry of Health, Rome, Italy

Professor Yutang Li, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, Nanjing University of Traditional Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China

Professor Emilio Minelli, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, Centre of Research in Bioclimatology, Biotechnologies and Natural Medicine, State University of Milan, Milan, Italy

Dr Nguyen Thi Kim Dung Director, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, National Hospital of Traditional Medicine, Hanoi, Viet Nam

Dr Susanne Nordling, Chairman, Nordic Co-operation Committee for Non- conventional Medicine, Sollentuna, Sweden [Co-Chairperson]

Dr Hieng Punley, Director, National Center of Traditional Medicine, Ministry of Health, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Dr Léon Ranaivo-Harimanana, Head of Clinical Trial Department in Centre National d’Application des Recherches Pharmaceutiques, Ambodivoanjo, Antananarivo, Madagascar

Ms Lucia Scrabbi, Planning Unit Directorate-General of Health, Lombardy Region, Milan, Italy

Professor Umberto Solimene, Director, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, Centre of Research in Bioclimatology, Biotechnologies and Natural Medicine, State University of Milan, Milan, Italy

*Dr Pennapa Subcharoen, Health Supervisor, Office of the Health Inspector, General Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand

Dr Chaiyanan Thayawiwat, Director, Hua Hin Hospital, Amphur Hua Hin, Prachuapkhirikhan, Thailand

Dr Sounaly Themy, Medical Doctor, Traditional Therapies, Traditional Medicine Research Centre, Ministry of Health, Vientiane, Lao People's Democratic Republic

Dr Yong-Jun Wang, Director, Orthopaedics Department, Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, China

Dr Jidong Wu, President, Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom

Professor Shan Wu Moxibustion Department Guangzhou Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province China

Professor Yunxiang Xu, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China

Professor Charlie Changli Xue, Director, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, Division of Chinese Medicine, School of Health Sciences, RMIT University, Bundoora, Victoria, Australia [Co-Rapporteur]

Dr Je-Pil Yoon, Director, Department of International Affairs, Association of Korean Oriental Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Dr Qi Zhang, Director-General, Department of International Cooperation, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China [Co-Chairperson]

Local Secretariat

Dr Maurizio Italiano, WHO Collaborating Centre for Traditional Medicine, Centre of Research in Medical Bioclimatology, Biotechnologies and Natural Medicines, State University of Milan, Milan, Italy

* It was with great sorrow that we learned of the death of Professor Subcharoen in April 2008. Her great contributions to the work of WHO, especially in the development of this document on basic training in Nuad Thai therapy, will always be remembered.

WHO Secretariat

Dr Samvel Azatyan, Technical Officer, Department of Technical Cooperation for Essential Drugs and Traditional Medicine, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Dr Houxin Wu, Technical Officer, Traditional Medicine, Department of Technical Cooperation for Essential Drugs and Traditional Medicine, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Dr Xiaorui Zhang, Coordinator, Traditional Medicine, Department of Technical Cooperation for Essential Drugs and Traditional Medicine, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland "

Plus d'infos:>>>